Can inflating grades, deflate learning?

I was recently engaged in an interesting conversation with a colleague at work that inspired me to write this post. We were discussing students’ and parents’ obsession with grades, how it occurred? Why it occurred? And how it has impacted students’ learning.

I draw upon my own experiences for this comparison, having attended an American University, both as an undergraduate (briefly) and as an instructor, I also attended Undergraduate and postgraduate courses in the UK. Reflecting on those experiences helped form some of my opinions on the notion of grade inflation.

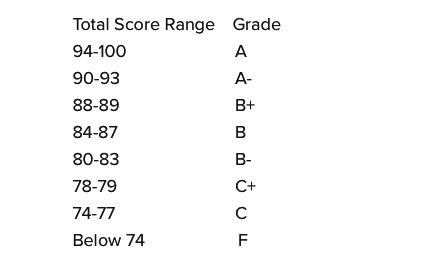

During my time as an undergraduate in a liberal arts American University, the grading system was as follows:

If we look at these grading ranges in an abstract manner, it literally translates to “any student receiving an A” is almost flawless in that subject area. Which follows the ‘norm’ that students would have experienced during their high school assessments. They are being assessed on the comprehension and memorisation of the knowledge relayed to them.

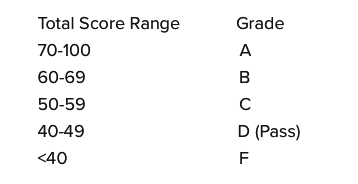

During my time as an undergraduate in a British University in the UK, the grading system was as follows:

I vividly remember my first day in class in the UK, being handed the syllabus and involuntarily letting out a small chuckle while thinking to myself: “I can get 40% without even attending!” and boy was I wrong!

This concept of 70% for an A was alien to me and I could not comprehend the rationale. I did not understand whether expectations were just lower in the UK, or whether the content was far more advanced. Eventually, I spoke to a few faculty members about this and added to them my reflections and experiences.

One faculty member that taught us an introductory Physics module, explained that if there was a physics student that was studying the theory of general relativity, keeping in mind this student was a very good student, would he be likely to score 100% on a test? He quickly answered that he wouldn’t. I was a bit concerned that this guy is just a tough grader. But he went on to explain, if a student understands the theory of relativity, they may be a good student, and hence can justifiably score an A on the test, however, unless the student ‘becomes’ a physicists and can critique, disprove or add to the theory, how can they be awarded top marks for just understanding a concept. He went on to add, how can you differentiate between a good student and a good physicists? How would I be able to tell if a student just memorised a lot of content (or even understood it) versus a student that may change the laws of physics as we know it, if they can both score 100% on a test?

He explained that the way they tried to operate was to allow for ‘A’ students to get what they deserve but allow for outstanding students to excel in their field. Bascially, the point he was making, that not every A student will be an Einstein and that our assessments should be able to reflect that. An opinion that I do not necessarily 100% agree with, but I do think is fairly rational when looking at all the talk about assessment.

This is a notion I often reflect on especially since I started working in an American institution with the same grading criteria (A= 94+). I realised that students have become more bothered about securing the 94% than being inventive or adding to the field. It was a matter of how to get to that grade, or which instructor is a lenient grader, rather than be about the learning or topic or interest.

I genuinely believe that this does not only harm the learning process during their time in formal education, but it also give students a false sense of over confidence, which leaves them far more vulnerable to disappointment upon entering the field of work. A student that has spent four years in university, with an average percentage of 99% cannot comprehend that their knowledge of their field is still fairly limited. How can it then make sense to students that there is still a lot for them to learn and keep learning, there is a lot to experience and a lot to develop, when for the past few years all the ‘records’ reflect their greatness in the subject?

This pressure to ‘get the grade’ extends to parents and sadly also teachers. Teachers and faculty members whose students are “underachieving” or have a lower average than students in other professors’ classes can be seen as under-performing. This restricts the faculty members from teaching how or what they want or see as more fitting to their students. It restricts their ability to differentiate on activities as well as, affecting the students ability to think critically about the material and encounter multiple perspectives.

I hope that those of you that are teachers, faculty members, faculty developers, course assessors who may have encountered both types of grading systems, would express your opinions on here. I do not have the authority to change the institution’s grading policy, but I am very interested to see if others have a similar view on the topic, or even a very differing view. Tweet your thoughts to @the_sosman